Daniel Lentz: Out There

Composer Daniel Lentz Is Not Necessarily a Bad Man

By Dave Shulman

First published in L.A. Weekly, July 11, 1997.

“Hello?”

“So how’d things go in the Czech Republic?”

“Fantastic, man. I got a half-hour standing ovation.”

“From the audience?”

“From the audience, asshole.”

“Wow. Why’d you come back?”

“I have no idea.”

DANIEL LENTZ IS BACK NOW, recovered — more or less — from the shock of being in a country where the arts are respected and attended with an enthusiasm that we here reserve for professional sports played between beer commercials and Schwarzenegger flicks. The ovation in question was for the premiere of Lentz’s Apologetica, performed last June by the Archbishop’s Ensemble and Choir at St. Moritz Cathedral in the Czech Republic.

A half-hour standing ovation is generally considered to be good, especially when the piece itself lasts only 60 minutes or so. Apologetica was performed and well-received again in December, this time in Kobe, Japan, on the same night Lentz premiered Temple of Lament, a composition for solo soprano, two MIDI keyboards and digital orchestra. Lament pissed off a few people there who felt that the libretto — the poetry of Yamanoue Okura, written in the 13th century or thereabouts — was not to be messed with, and certainly not to be set to music by some scraggly Western intellectual type.

But he’s back now, back in his Arizonan Boondockia, out Phoenix way, in a fine strange house designed by Will Bruder, the man equally responsible for the new Phoenix Central Library. “The first art I’ve ever lived in” is how Daniel put it on move-in day, April Fools’ Day 1992. He’d been in Phoenix a year at that point, about six months beyond my imagination. (Phoenix to me is Orange County with more beach and less ocean.)

In case you’ve been following something other than Lentz’s career: An excellent chef, he was the first American awarded First Prize in the Stichting Gaudeamus International Composers Competition in Holland, the first-ever recipient of a Fulbright Fellowship in electronic music and the first Los Angeles classical composer since Stravinsky to be signed to a major record label (Angel/EMI). Just a fine, fine, really good cook. Daniel’s especially known for his creation and use of live multitrack recording: In performance, the live music is recorded, synchronized and then played back as layer upon expanding layer of ever-multiplying sound. Librettos are sung as phonemes — a true pain in the ass for vocalists — which, when played back/performed between and upon themselves and each other, come together as words and then phrases and then entirely different phrases, all transfiguring from the middle outward. His osso buco is flawless.

So it’s convenient, after the six-hour drive, to find him preparing dinner, surrounded by seasonings and two bottles of wine, uncorked.

“What kind of wine is that?”

“One’s red and one’s white.”

“Ah. My favorites. Which is — the red one’s the darker one?”

“Yeah.”

Daniel has a close personal relationship with wine. In 1984’s Bacchus, which was performed around the world, including here in L.A. at the now-defunct Wallenboyd Theater, the spirited performers — six of ’em, seated at a plain, rectangular table — created all non-text sounds by striking and rubbing variously filled and hotly miked wine glasses, drinking and pouring wine as necessary to achieve the proper pitch. The text was a bunch of wine clichés: He who gets drunk and laid and makes music is not necessarily a bad man — something like that. So there you sat listening to these caverns of sound, deep and high, filling with wild swelling harmonies broken by crisp glances off crystal, watching this rubbing and striking and pouring and drinking. As much as any piece of 20th-century music, Bacchus patched the insidious gap between wine-as-religious-ritual and sitting at a plain, rectangular table on a stage, getting plastered.

***

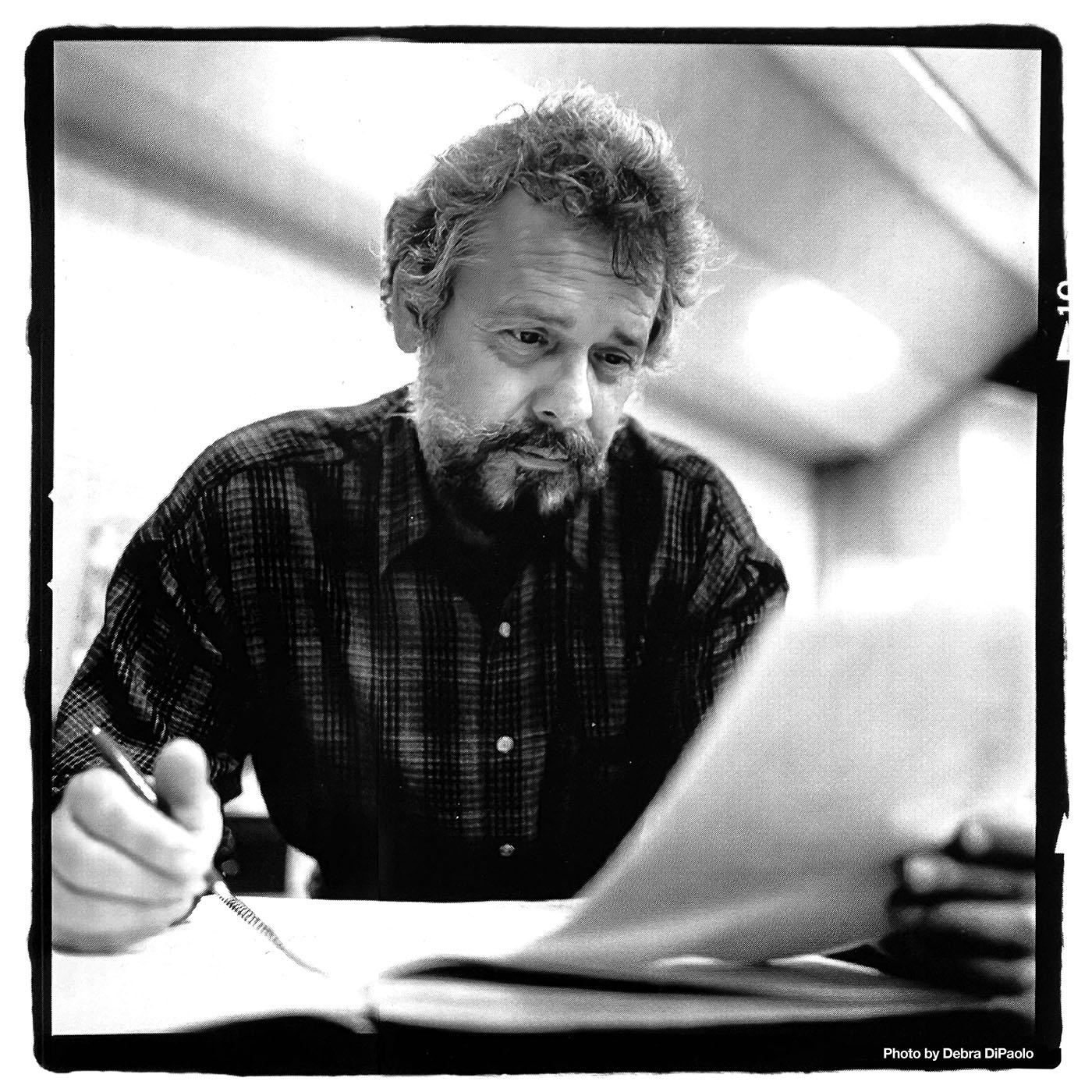

Talk, eat, drink, drink. After dinner, we sit at an old sun-tortured dining table out on the patio with a couple of bottles of wine; good thick wine. In our 14 years of friendship, this is the first time we’ve ever talked across a 1986 Sony TCM-27 standard cassette recorder and its Time Index Recording™, auto-stop, cue marker and durable nylon wrist strap. Daniel — looking a bit sun-tortured himself, though otherwise a dead ringer for Debussy — looks over my notes.

“I haven’t answered any of these.”

“Well, technically, I haven’t asked any of them.”

“Maybe I should say something intelligent.”

“Why? I never do.”

“Well, you’re a writer — you can get away with it.”

“I thought you just said you weren’t going to say shit like that.”

“Shit like what?”

We sit and stare into the desert.

***

The subversively beatific anarchist so focused on his artistic path that communication without satire is difficult or impossible: This is the Daniel that tends to occupy the composite Daniel most often. Sometimes, though, he’s just a sort of hard-working Pennsylvanian cursed with a lethal level of awareness several times over. Daniel’s probably the most aware person I’ve met who hasn’t gone entirely out of his mind.

Since his ’60s experimentation with political/electronic music, and after he was dismissed from a cushy teaching post at UC Santa Barbara in 1969 (his piece for the faculty recital included people fucking in a piano), Daniel’s voice emerged as something that has generally been thrown in with the Minimalists, though its emphasis on melody and mutability defies the category.

“In about 1968,” Dan says, “I turned against the [makes ’50s sci-fi electronic beedly-bweeps] stuff and started to write ’pretty’ music. And I can remember the reception I’d get in places like Germany and Sweden.”

(Not good.)

“Because they hadn’t heard ’pretty’ music since Debussy. Before then, I’d been doing that conceptual bullshit, political music and all that, and they expected to hear the same old thing. To land there with ’pretty’ music was unthinkable. And I hear Górecki got the same in ’76. Only he was in Eastern Europe, so I can imagine the reaction was even stronger. And then the Zinman recording [of Górecki’s Symphony No. 3] went up there — 6 million copies, I think. So now he’s the only guy in this small Polish town with a Mercedes.”

“He still lives in the same town?”

“From what I understand, he’s never moved from his little coal-mining town. I don’t know where in the hell he gets his car serviced.”

“What about Arvo Pärt, another practitioner of . . . what do I call it? New Anti-Tech music?”

“He’s just another one of those guys born 500 years too late. Same with Gavin Bryars, the English guy who did that Jesus piece [Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet]. And there’s a couple other English guys . . . . I like it. All that MIDI stuff’s getting boring.”

Please do not confuse the “pretty” music of which we yammer with so-called New Age or ambient music.

“What do you mean by ’ambient music’?” Dan asks when I threaten to drink more wine. “Brian Eno and that kinda stuff? I mean, he’s the one that called it ’ambient.’ And that’s the only time it worked — the first time. Music for Airports and shit like that. ’Ambient music.’ Hm. I get a massage every once in a while, and that’s what the masseuse plays, this ambient music with little birds and bad harps.”

“You mean a real massage, or one of those like in the ads at the back of the Weekly?”

Which brings up all the ads for pop music and that brings up ads in general. And we talk of war and of popular music, because we talk of the music played at night by the people whose day jobs are to kill and die for our right to sell advertisments for the music they listen to.

“Still,” I say, “I like some rock-style music. It’s the sonic equivalent of looking at wallpaper, versus looking at art. Sometimes looking at wallpaper keeps you from thinking about the actual wall, you know? And then I’ll go a stretch — maybe a month or two — without rock, and when I hear it during that time — spilling from someone’s car or something — I can’t imagine why I’d want to hear it. And I’ll feel sort of sad, knowing that for some reason I will, and that, because pop is the only kind of music most of us are exposed to, most of us look at the wallpaper thinking we’re looking at art.”

“What lemmings are to nature,” Daniel says, “rock is to music. You know, that’s the big difference between L.A. and here. Here, I don’t have to hear it. It’s a non-issue. I was consumed by it in L.A. Because it is everywhere there. The elevators play rock & roll. You open the L.A. Times . . . I remember [composer] John Harbison telling me the reason he wanted to leave L.A. was because of the L.A. Times. You open the Calendar section, it’s all about movies and rock & roll. There’s nothing about art. Or very, very rarely. William Whatsisname.”

“William Wilson? Is that his name?”

“Yeah. He’d have an occasional piece that was interesting.”

“William Wilson, Kristine McKenna and . . . Christopher . . .”

[In unison] “Knight.”

“Yeah, they infused a little light into it. But musically it was just awful. The option was Bernheimer. There was nothing else . . . But yeah, rock — you don’t hear it here.”

“Even in town, in Phoenix?”

“I don’t go into town. If I go into town it’s to New York.”

[In unison] “That’s ‘in town.’”

***

Seeing that there’s plenty of desert still to look at, we do. And we drink quietly and breathe and sit and smoke cigars (which we can’t be seen with in public anymore, now that they’re “cool”) and just watch the available world ingredients.

I say, “Why do you think you do what you do, whatever that is? Specifically: You have a voice, or whatever you want to call that. Whatever you want to call anything, right? Someone commissions you to do something, and they get a Daniel Lentz piece, without you feeling as if you’ve had to conform to something; you’re just getting paid to make your art. So what is that voice?”

“I guess change.”

“Yeah?”

“You know, the notion of style, which is recognizability, where you repeat what you’ve done before, and then you get a recognizable style by doing that over and over and over and over . . . The best-known musicians in this world — this so-called ’art music’ world — are the ones who’ve been doing the same thing for 20 or 30 years. And then there’re the very few who change — like a Górecki: There’ve been some really dramatic changes in his music.”

“And those staying the same would be . . .?”

“I don’t want to mention names. You’ll print them.”

“Yes . . . and . . .?”

“There are things Reich’s done; Reich’s made some subtle changes. I never really thought of him as being particularly musical; I don’t think his music is about being music. It’s about something else. It’s about . . . being in New York. Maybe he should’ve been a painter. He’s closer to Donald Judd than he is to Stravinsky or Cage. You know what I mean? Musically, it’s limited. If you want a comparison, I much prefer Philip Glass. Philip’s more musical. And that’s a simple fact. Maybe he’s not as interesting intellectually, but it’s more musical.”

“It’s funnier.”

“Ah, I don’t want to get into this.”

“All right, all right. Let’s talk about self-sabotage. It seems like, ever since I’ve known you, periodically Critic This or Magazine That would write some big article about you, implying that you’re about to be this real big famous composer guy, and then you wouldn’t be. That seemed to happen somewhat regularly.”

“Yeah. I think that’s very important, absolutely, you know, not to do that.”

“Not to get famous?”

“Yeah. Or maybe I’d be ready for it now — I certainly wasn’t then.”

“Fame would make you stagnate?”

“Yeah, I think so. You get locked into an expected sound, you know, and that’s what you’re ending up getting the big bucks for; you gotta do it again.”

“And again.”

The front door opens; it’s this real big famous composer guy, Harold Budd. He’s staying at Dan’s while recording out in Mesa, about an hour away. Harold’s beat and heads straight for the food (“Bitchen. Thanks.”); Daniel and I continue with our fabulous interview.

“What is the next piece, the one based on the last part of Apologetica?”

“Actually, I just finished a couple of them. But the next one is a commission from Japan; I have to make a piece for Aki Takahashi, the keyboard player. It’s for her, a voice soloist, another keyboard — playing other kinds of things — and then a string orchestra. And what I want to do, I want to explore what Apologetica is, a little bit more. These glissandi, you know, where nothing is ever anywhere, harmonically? Always somewhere else.”

“No home base, basically?”

“No. Never goes anywhere but up. And that’ll be about 20 or 30 minutes.”

(The piece, Temple of Lament, ended up in three sections: the first of glissandi up; the second glissandi up and down and all over; the third all going down. It’s an amazing piece of music, and listening to it now, as I write, brings up an important point: I don’t listen to Daniel’s music every day or week or even month. Sometimes it’s two or three months between listens. But when I do, that’s all I do; that and maybe cry — the kind of cry you have when you remind yourself that everything you’ve been taught is only that: stuff you’ve been taught.)

***

It’s downright dark out now. A big moon rises softly behind clouds. Night animals scuttle in the mesquite. I can’t believe how quiet it is.

“I can’t believe how quiet it is here.”

“Yep.”

And then a fucking chicken ruins it.

“Well, there’s the chicken.”

“Later you’ll hear some coyotes.”

Dan lights a fresh cigar. “It’s not so important anymore to be somewhere — in the city/state sense — you know what I mean? It doesn’t really matter where you do your work. Like it used to. You had to be in New York in the ’40s and ’50s — you had to; nothing else happened outside of that. And then it spread to the West Coast a little bit . . .”

“Where would you live at this point, if you could?”

“Ireland.”

“Maryland?! Why Maryland?”

“I said ’Ireland.’”

“Oh. Why Ireland?”

“I like Prague a lot, but I don’t speak the language. I speak a little bit of Irish. I can say ’Guinness.’”

***

“Well, I hope I interviewed you.”

“I’m still waiting to say something intelligent.”

“What kind of wine is that?”

“One’s red and one’s white.”

“Which is — the red one’s the darker one?”

“Yeah.”

“Oh, yeah. No wonder it tastes . . .”

“Warmer.”

“Right. Yeah.”

“Like blood.”

“Because we’re in the desert.”

#